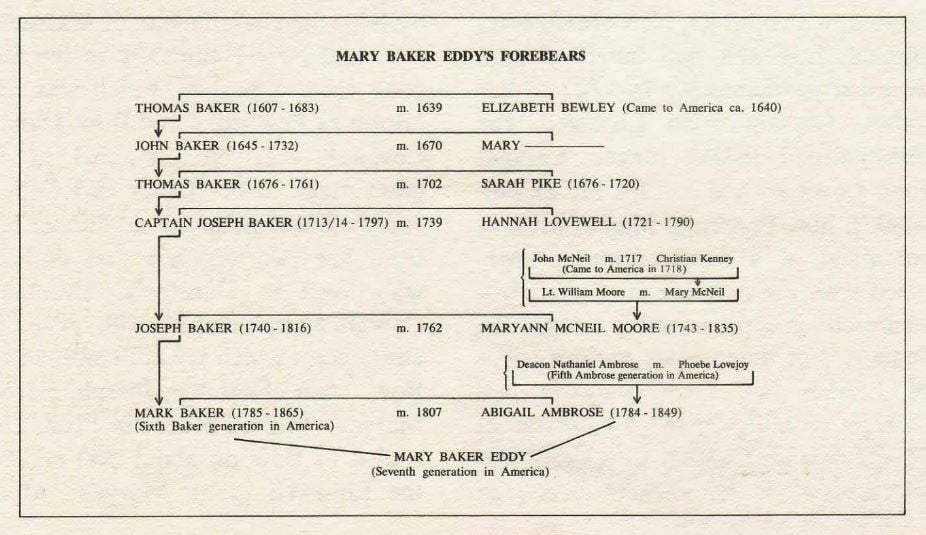

Mark Baker was no farmer at heart. Although a son of the land, he was also heir of a long line of ancestors who had left imprints on their environments. His English ancestors were among the sturdy yeomen of Kent during the stirring activities of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries which wrested a measure of civil and religious freedom from the autocratic hands of King and Church.

Some became Protestants and about 1640 Thomas Baker, who had been baptized in Elmstead but later lived in Ashford, County Kent, came to Massachusetts after his excommunication by the Diocese of Canterbury for nonconformity to Church requirements. He had started a life in Kent with a patrimony of about eighty-five pounds and as a miller he doubtless increased this by the time he started for America. He settled at Roxbury, not far from his brother Richard and his nephew John, who had preceded him by some three years. By 1652 he was operating his own tide-mill in the Roxbury area where for more than a hundred years prior to the American revolution the Baker family were respected freemen and had acquired considerable land from the government of Massachusetts in recognition of military service and by purchase.

When Captain Joseph Baker, a third generation descendant of Thomas, married Hannah Lovewell in 1739, he left his comfortable home in Roxbury, and the young couple journeyed seventy-five miles north into the wilderness of Suncook, now Pembroke, New Hampshire. Hannah Lovewell had inherited land awarded posthumously in 1727 to her father, Captain John Lovewell, the distinguished Indian ranger. Captain John Lovewell had lost his life at Pigwacket, now Fryeburg, Maine, while in command of a small company organized with the permission of the Massachusetts general assembly to fight the Indians. For many years various tribes of Indians had made frequent and destructive raids on the settlements of New England. Captain Lovewell’s first successes along the northern reaches of Lake Winnipiseogee (Winnipesaukee) encouraged him to strike at Pigwacket, headquarters of the Indians on the Frontier. Lovewell’s men were greatly outnumbered, and despite heavy losses inflicted on the Indians, many of the company were killed, including the intrepid Lovewell himself. Although a defeat, the battle broke the power of the Indians and destroyed their commander, Paugus, who had not only incited the Indians to raid the settlers, but had himself been spurred into action by the French, who coveted the rich New England area.

In recognition of their bravery, Captain Lovewell and the men who served him, were awarded grants by both the governments of Massachusetts and New Hampshire in the Suncook area, a part of which was later known as Pembroke and Bow. Hannah Lovewell received one-third of the grant made to her father and Captain Joseph Baker acquired additional land from her two brothers and co-heirs, who lived in Dunstable. Eventually Captain Joseph and his wife owned the entire grant which lay in Pembroke and Bow. Their eldest son, Joseph, married Maryann McNeil Moore in 1762. They settled in Bow on about 500 acres of the Lovewell grant. Maryann Moore (or Moor) was the daughter of Captain William Moore and Mary McNeil, whos parents were John McNeil and his wife, Christian Kenney McNeil. In the mid-seventeenth century, John’s grandfather along with other members of the clan McNeil had crossed from their native Scotland to northern Ireland and settled there. John and his wife emigrated from Ireland to America in 1718.

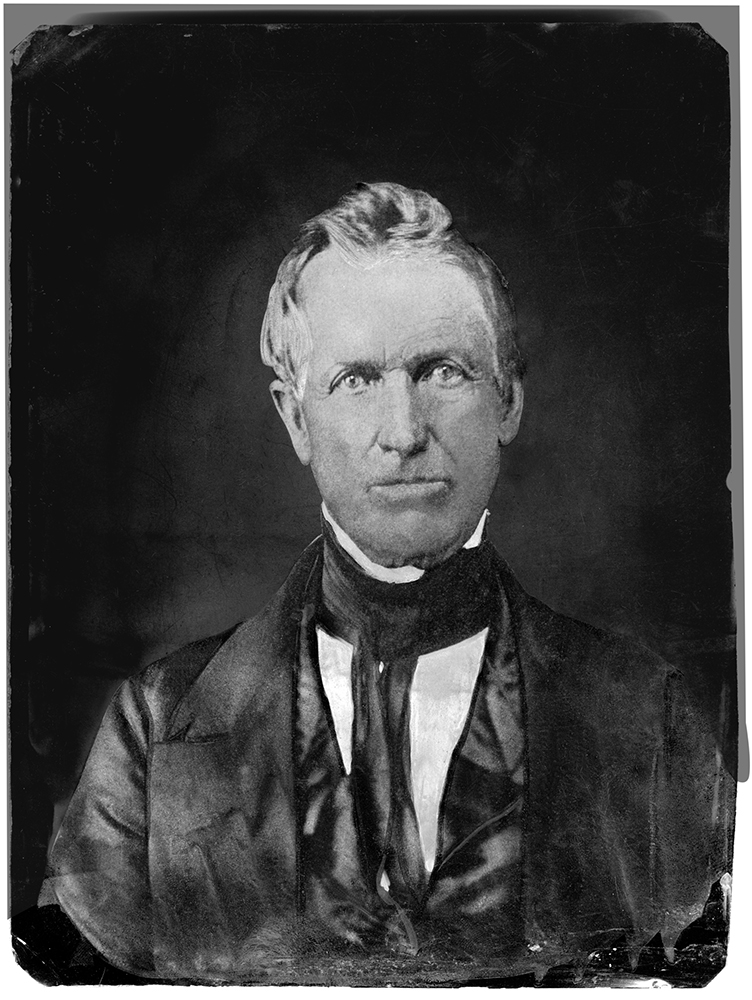

Mark Baker, youngest son of Joseph and Maryann Baker, was born in 1785 on the homestead familiar now to so many as the birthplace of Mark’s youngest daughter, Mary Baker Eddy. The house had been built by Joseph, who also brought the land under cultivation. Mark lived with his father and mother and brought up his young family in the old Baker house. From his earliest days Mark Baker was in close touch with community matters in which his father and grandfather participated. Both Joseph and his father, Captain Joseph, were active in their local churches, Captain Joseph at Pembroke and Joseph at Bow. Both served as selectmen in their communities and both were collectors of provincial revenues. During the Revolutionary War, Captain Joseph, then beyond the years of active service, was elected a member of the Committee of Safety for Pembroke. His son Joseph was one of forty-eight men of Bow who volunteered to serve in the Revolutionary War, but he seems not to have been called.

Captain Joseph surveyed the land grants of Pembroke and Bow, which overlapped because the grants to Pembroke were made by the government of Massachusetts and those to Bow by the government of New Hampshire.

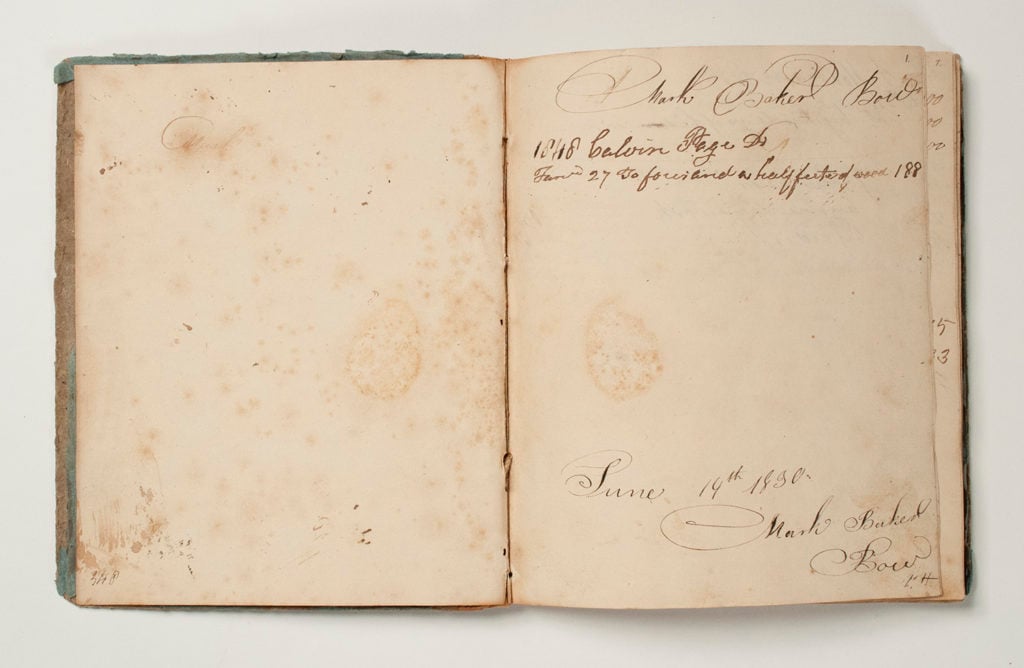

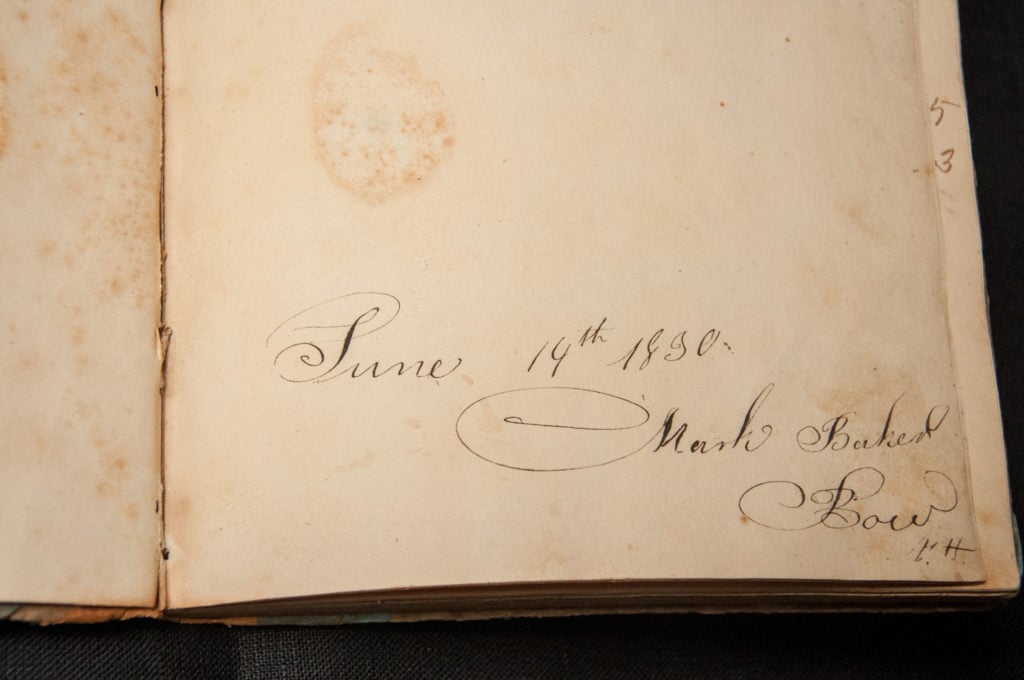

As he grew to manhood Mark Baker came naturally to a position of responsibility in his community. For many years he was agent for the poor and was Coroner for Rockingham County, which then included Bow. He served on the school board, was moderator of town meetings, and Clerk of his church. Repeatedly he acted as official agent for Bow and helped settle the annual business of the town. Later, in Sanbornton, he became Justice of the Peace for Belknap County.

None of his children wished to make farming a life work and one after another of his sons chose other occupations — Samuel, that of mason, George Sullivan, of wool specialist and businessman, and Albert, of attorney. Mark decided in 1835, after his mother’s passing, that it was time to take a smaller farm in another community where the family would have better educational advantages and a more interesting life. He moved to Sanbornton Bridge in 1836. His son Albert wrote of his brother George Sullivan on August 23, 1836: “Indeed I see no reason why he (Father) may not be satisfied. He lives in the neighborhood of two sanctuaries — a matter of great moment — two academies, a very pleasant village, society agreeable, etc. etc.”