When carefully laid plans finally spring into action on any construction project, unexpected challenges can literally come out of the woodwork. The restoration of Mary Baker Eddy’s home at 400 Beacon Street was no exception. Given the scope and importance of preserving the house for generations to come, a dedicated team stood ready to tackle each situation as it arose.

Early on in the project, the Longyear group forged “a genuinely collaborative” process that was “extraordinary,” says consultant Chris Milford, who served as owner’s project manager— representing Longyear’s interests throughout the restoration. An architect by training and a veteran of numerous construction projects, he notes that “the general effort was to find solutions to problems. … There was no finger-pointing.”

When Chris first joined the team, Longyear Executive Director Sandy Houston shared with him a phrase from Mrs. Eddy’s writings that guided Longyear’s approach: “wisdom, economy, and brotherly love.”1

“The ‘brotherly love’ component was completely unfamiliar to me in the context of construction, and it changed the way I dealt with people,” Chris says. He kept the phrase posted by his desk. “I would love to put it on every set of construction documents I ever produce! … It gets people focused on, let’s work together and be smart. Let’s pay attention to the money—it’s important to everybody—but let’s do it in a way that we respect one another.”

Mrs. Eddy’s words proved to be a practical framework for guiding decisions each step of the way, especially when circumstances impelled the group of architects, engineers, contractors, and Longyear staff to pause or shift in a new direction.

A Firmer Foundation

A significant structural issue with the carriage house required the team to devote substantial time and thought to developing a safe and lasting solution. Cracks in the building indicated that the west facade was falling away from the rest of the structure. Decades before, a metal rod stretching from the east wall to the west wall had been installed in the hayloft as a stopgap measure. It had been equipped with a turnbuckle system to help hold the west wall in place. But now a more permanent solution was needed. The greatest care would be required to stabilize the three-story wall that weighed roughly 60 tons.

As the architects and engineers studied the situation, it became obvious that three of the carriage house walls rested on solid rock. Soon some team members began to suspect that the west wall was resting on soil.

Ground-penetrating radar and soil-boring tests confirmed that theory. The geotechnical engineers encountered 13 feet of soil before they hit bedrock—soil that could not be counted on to support a 60-ton structure. The priority was to “stabilize everything to prevent further settlement of the building,” explains Benjamin Lueck, the project manager from the architectural firm overseeing the restoration, DBVW Architects.

To support its massive weight, the west wall needed a new foundation. Installing the foundation would necessitate both wisdom and brotherly love, with extraordinary consideration for the safety of the workers involved.

First, workers drilled down and inserted micropiles (heavy steel tubes filled with grout) that rested on the bedrock below the wall. These micropiles were placed in rows along the outside and the inside of the wall, and steel I-beams were laid on top. Then the crew bored 12-inch holes through the wall and placed temporary steel needle beams through the holes. With the needle beams resting across the I-beams, the weight of the wall was now supported. This enabled the team to remove a portion of the wall below ground level and pour a new concrete foundation, encasing the micropiles. The new structure distributed the weight of the wall on the bedrock.

For safety, the crew excavated only three feet of the wall at a time—adding the new foundation gradually in small sections. “It was a very carefully planned process … and the contractor went one step beyond” to protect those involved, Chris says. They set up a vibration-monitoring system so that “if there was any shifting [of the wall], down to a fraction of an inch, they would know immediately.”

After pouring the new foundation, the workers removed the needle beams and refilled the holes with rock and mortar. On the exterior, they covered the filled holes with stone that matches the rest of the wall, so it looks as if nothing was changed.

“It was one of the more delicate procedures,” Ben says. “Any time you have an entire side of a building supported on a temporary structure, whenever you can remove that temporary structure, there’s a huge sigh of relief.”

Shoring up the west wall of the carriage house was a complex undertaking that took about six months to complete, but it provides a long-lasting solution that has stabilized the building for decades to come. “That decision-making process, ‘What’s the right thing to do for the next generation?’ came up regularly,” Chris says.

‘Brotherly Love’ for Visitors

Ideas often emerged through studying historic photos and documents—and by asking a lot of questions. One such solution involved a new stairway that starts in a former closet on the first floor of the main house and proceeds down to the basement—which has been beautifully transformed into an exhibit gallery. (The fall ’24 issue of Longyear Review will cover the new exhibit about Mrs. Eddy and her household.)

When the staircase was first installed, Director of Facilities John Alioto, Longyear’s on-site representative throughout the project, noticed that some people were nearly hitting their heads on the ceiling as they got to the landing. A portion of wall—thought to be load-bearing—was preventing the stairs and landing from being extended to a more comfortable level.

Not satisfied with visitors having a less-than-optimal experience on the staircase, John began to investigate. Earlier, he had examined a photo of the original 1880s house that showed the front facade as clearly different from the way it looks today. The roof line had been changed when the house was remodeled for Mrs. Eddy in 1908. He knew the wall in the basement stairway had originally extended all the way up through the house to support the roof, but given the changes to the building in 1908, John began to wonder whether it still was load-bearing. With further investigation, he found that where load-bearing walls should have been on the first and second floors, there were doorways.

After he shared this observation, the team verified that the wall in the basement stairwell was supporting nothing more than the floor joists in the hallway just above it. They removed most of the wall, which enabled them to extend the stairway and provide more headroom for visitors. “They reengineered the stairs, and we now have a gracious descent with plenty of headroom,” John says.

Ductwork Choreography

Adding modern mechanical systems to the house presented several puzzles to solve.

Installing ductwork for a new air-conditioning system creates challenges in a historic house when there is a desire no to alter interior spaces. At 400 Beacon Street, the installation work proceeded as planned on the third floor (where new ductwork was installed in the attic). On the second floor, however, the team’s plan to lower the hallway ceiling and route ductwork above doorways ran into an unexpected roadblock: old style trusses (wood placed at an angle) that formed triangles too small for ductwork.

It wasn’t a surprise to be surprised, Ben Lueck says. “You’re always going to be working on the fly to adapt to the existing conditions as they are exposed during construction.”

Adapting in this case meant effective communication about how to build headers to replace the trusses, create enough space for ductwork, and still carry the load. “Everyone saw it as an interesting problem to work through,” Ben adds.

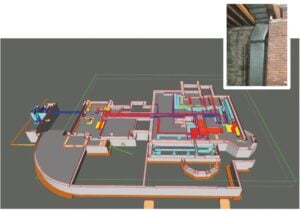

Routing the HVAC system through the basement exhibit space was even more complex: The ductwork was distributed under the raised floor, bending around or over the steam pipes, plumbing pipes, sprinkler lines, and floor supports, and snaking up the walls and through the ceiling into the first floor.

The team wanted to verify whether everything would fit, so the contractor created a digital 3-D model that showed “how carefully choreographed these different utilities had to be,” Chris says.

The model revealed a problem, though. Where ductwork was supposed to run up behind a wall and fit into the basement ceiling between the joists, it did not fit. In modern construction, standard spacing between floor joists is typically 16 inches, but when this house was built, the joists were placed every 12 inches. The new ductwork was 14 inches wide.

It was one of those moments early in the process when Chris witnessed the team working professionally and respectfully, expressing that sense of brotherly love. Early demolition had revealed this condition, but the design documents had never been changed to show the narrow width between the joists. “On a typical construction project, everybody would have been pointing fingers at everybody else,” because addressing the situation would involve an additional expense, Chris says. “But that didn’t happen.” The team worked together to restructure the joists, removing one and reinforcing the remaining ones. Longyear paid for the structural engineering needed to solve the problem, and the contractor agreed to dip into their contingency funds to cover the construction costs. It was resolved harmoniously.

Following Mrs. Eddy’s instructions about wisdom, economy, and brotherly love “wasn’t an academic exercise,” Executive Director Sandy Houston says. “We were striving to demonstrate the teachings of Christian Science, and we reaped the blessings.”