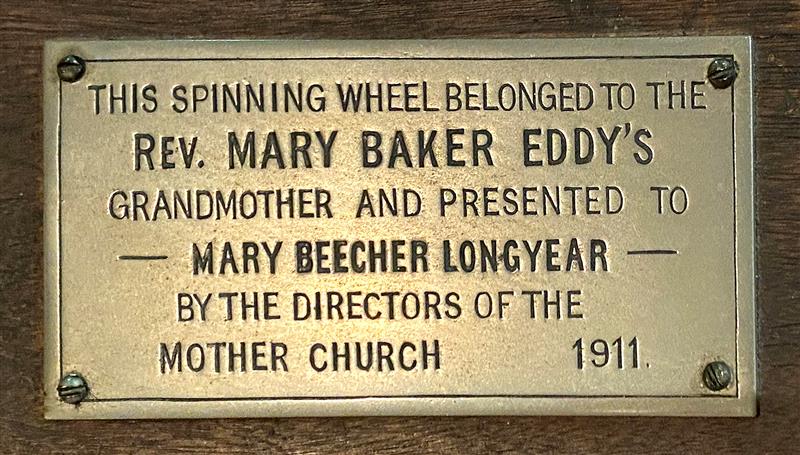

Tucked in a corner near the entrance to Longyear’s Mott Gallery is a vignette containing a number of objects from Mary Baker Eddy’s girlhood home. At the forefront of this grouping is a spinning wheel that belonged to her paternal grandmother, Maryann Baker.1 Pausing to view the display, a visitor might draw from it the simple lesson that Mrs. Eddy lived long ago. But this artifact, and the story of its connection with her early life, has much more to tell us about the world she experienced. A silent witness to the technological changes that transformed society during her lifetime, as well as a reminder of family connections that may have motivated its preservation, in its historical context the spinning wheel may also serve as a metaphor for the historical significance of Christian Science.

Standing 58 inches high, Maryann Baker’s spinning wheel would have dominated the kitchen of the Baker’s home in Bow, New Hampshire.2 It’s called a “walking wheel” as its operator would walk constantly back and forth while using it. Adapted specifically to spin the twisted fibers of wool into fine yarn, the wheel suggests that raising sheep may have been an important part of the Baker family’s farm production.

Mary Baker Eddy’s grandmother, Maryann Baker, and mother, Abigail Baker, would have operated it by setting the large wheel into motion. This would transfer energy through a cord to swiftly rotate a spindle that would then twist the raw wool into yarn. The operator would gradually move back, drawing out her line of yarn. When she had gone as far away as was convenient for her, she would reverse the motion of the wheel, walking forward as the newly spun yarn wound onto the bobbin. Then she would repeat the process.3 It is possible that a child or other assistant would be tasked with spinning the large wheel and changing its direction, but this helper had to stay focused in order to coordinate the motion efficiently.

As an artifact, the spinning wheel is aesthetically pleasing for its simple, functional design and for the craftsmanship evident in its construction. It is almost entirely made from wood, including several precisely-turned adjustment screws. Its most dramatic feature is its primary wheel. At 44 inches in diameter, the rim of the wheel was fashioned from a single thin strip of wood that was bent into a circle and spliced together. Two things are required to create such a wooden hoop: A truly skilled woodworker and a piece of absolutely flawless lumber over eleven feet long. Such high-quality wood is now exceedingly rare, but it was easily obtainable at the time the spinning wheel was crafted well over two centuries ago.

Growth of the textile industry

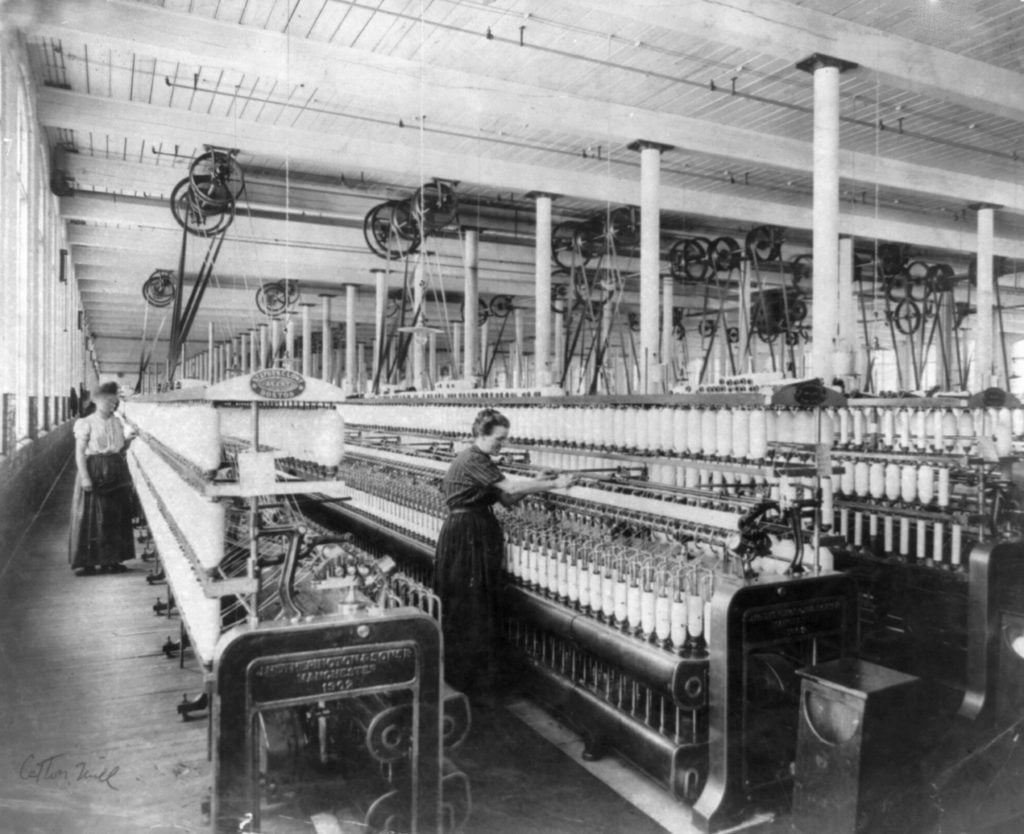

By the time Mrs. Eddy was a young woman, the spinning wheel was obsolete technology—a remnant of a by-gone era. Later in life, she recalled her mother spinning during her childhood, but as she was growing up in the 1820s and 1830s, spinning machines in new factories were rapidly replacing earlier methods of producing yarn and thread for textiles.4 The spinning wheel was still potentially useful, but its utility was akin to that of the rotary telephone and the manual typewriter today—still functional but largely superseded in everyday use. In fact, by the second half of the 18th century, British and European manufacturers were already using automated spinning equipment to produce factory-made textiles.

In the years immediately following the American Revolution, entrepreneurs began harnessing the waterpower of New England’s rivers to drive mechanized looms and spinning machines. By the time of Mrs. Eddy’s birth in 1821, the growing textile industry was a major element of the Industrial Revolution in North America. Decades later, Mrs. Eddy pasted a humorous New England chronology entitled “The Pilgrim’s Progress, 1620-1875” into one of her scrapbooks. She penciled in a bracket to mark the entry for 1791 which reads, “Starts a cotton spinning factory.”5 In making this notation, she may have been thinking about her family’s involvement in the textile industry.

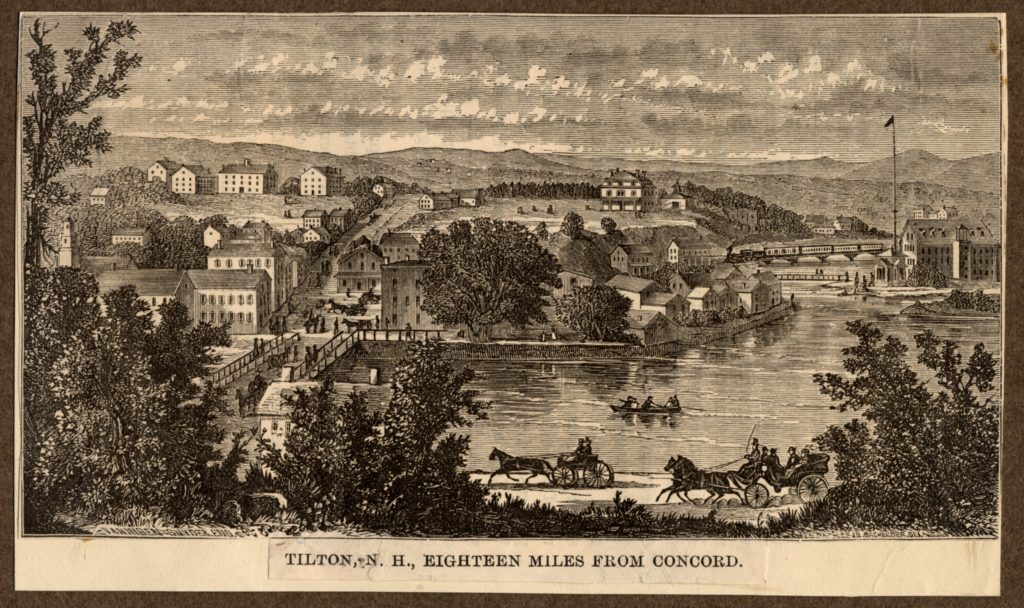

In 1837, Mary’s sister Abigail married Alexander Hamilton Tilton, scion of a prominent New Hampshire family that gained much of their wealth from the textile mills they owned. The following year, her brother George Sullivan Baker entered a partnership with his new brother-in-law to jointly operate textile mills along the Winnipesaukee River in Sanbornton Bridge.6

In Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896, Mrs. Eddy shared an anecdote about an incident at the mill that her brother George operated. One of the workers pulled a practical joke on an applicant for employment, directing the newcomer to pour water over the regulator every ten minutes. “When my brother returned and saw it, he said to the jester, ‘You must pay the man.’” Mrs. Eddy concluded the story by bringing out an important lesson: “Some people try to tend folks, as if they should steer the regulator of mankind. God makes us pay for tending the action that He adjusts.”7

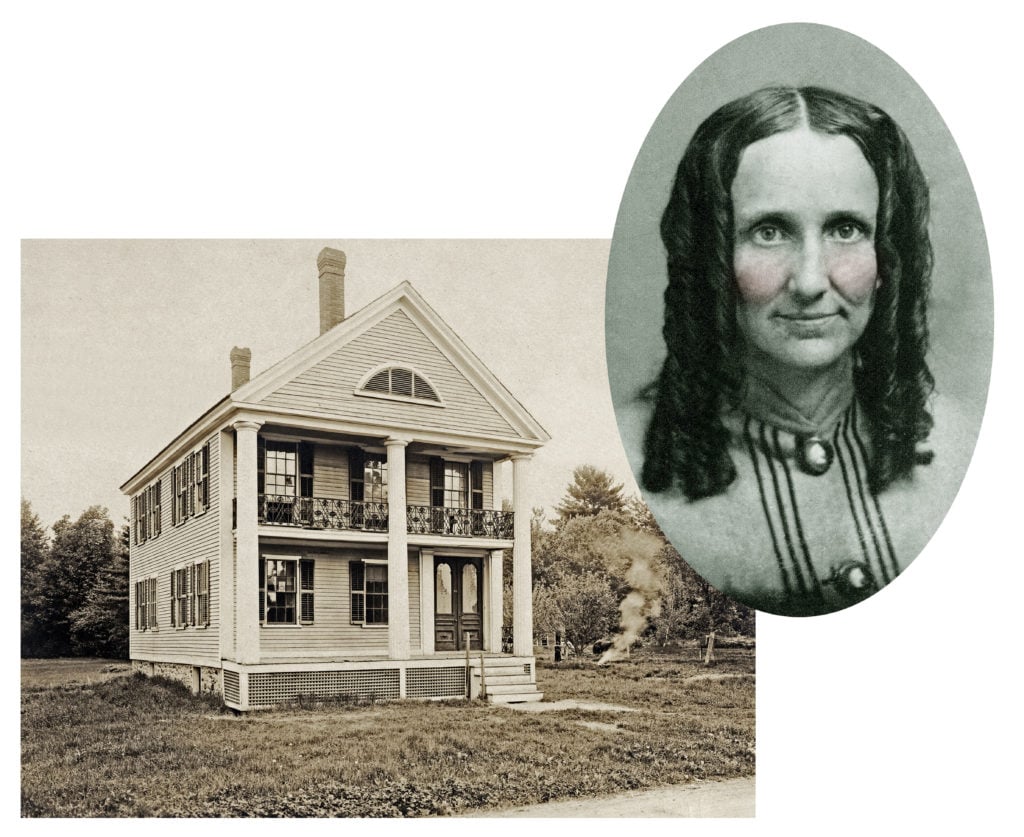

As it happened, George Baker also played a role in preserving his grandmother’s spinning wheel for future generations. When his father, Mark Baker, died in 1865, George inherited the family home in Sanbornton Bridge. His grandmother’s spinning wheel was part of its furnishings. After George’s death in 1867, his widow, Martha Rand Baker, kept the spinning wheel until her own passing in 1909, at which time the Christian Science Board of Directors acquired it from George and Martha’s son, George Waldron Baker. In July 1910, the directors offered it as a gift to Mary Beecher Longyear.8

While no historical evidence remains as to why George and his wife kept this object, it’s possible that the family’s connections to the textile industry gave it sentimental appeal. By the mid-nineteenth century, old New England spinning wheels were coming to be prized as emblems of a simpler and more virtuous era.

Nostalgia for the “Age of Homespun”

In 1851, while the widowed Mary Baker Glover was living with her sister Abigail Tilton and struggling to find a home where her young son would be welcome, Horace Bushnell, a Connecticut minister, gave an address celebrating the “Age of Homespun.”9 He, and others like him, presented a narrative of rugged Puritan families migrating from Great Britain to New England during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. These settlers, along with the communities they built, were praised by 19th-century commentators for their self-sufficiency. In the “good old days,” men felled mighty timbers and cultivated the ground, women cooked and made clothing for their families, and children helped with chores and learned to emulate their elders. All labored to the glory of God. The settlers were praised for taming the wilderness and laying the foundations of a great nation.

This idealized vision of the past omitted several elements, including the continuing presence of Native peoples, the work performed by indentured and enslaved laborers in colonial New England, and the fact that the colonists always participated to some degree in a market economy. Even in the most isolated colonial settlements, household production worked hand-in-hand with labor-specialization and a barter economy. From the earliest years of European settlements in America, men often specialized in occupations such as carpentry, ironworking, or preaching the Gospel. Women served as homemakers and partners in family-based enterprises, and they, too, often had their own specialized activities. One woman might be an excellent baker; another might own a loom and be a highly skilled weaver; yet another might serve as a midwife who assisted with childbirth and other nursing needs. All understood the basics of spinning, but for some it was a primary vocation while for others it was an occasional task. The members of each colonial household produced goods and services to meet their own needs, as well as for exchange with their neighbors.

By the end of the 1600s, the towns and villages of New England were becoming integrated into a large and growing economic system. They sold surplus food products to the slave-based colonies of the Caribbean in exchange for sugar, molasses, and rum. They built sailing vessels and shipped timber across the Atlantic. They traded a wide variety of goods with Native Americans along their northern and western borders for furs and other products. And they eagerly bought luxury items from Great Britain, Europe, and Asia, including tea, glass, porcelain, and fine textiles made from linen, wool, and silk. Seventeenth and eighteenth-century New Englanders had far more options for their garments and other textiles beyond the output of their own spinning wheels.

During periods of political disputes with Great Britain (running for about twenty years starting after 1763 and again during the War of 1812), American leaders emphasized the importance of local production as an element of independence and discouraged citizens from buying manufactured goods from the enemy.10 These conflicts hastened the development of New England’s textile mills. The rapid expansion of the cotton-growing economy in the south further boosted the textile industry, relegating home spinning to earlier generations.

In praising colonial goodwives who worked diligently at their spinning wheels, 19th-century commentators gently chastened the middle-class women of their own time. In their view, these women, in their pursuit of material comfort and elevated cultural attainments, had abandoned the virtue of contributing skilled manual labor to the support of their families. Instead, shifting cultural mores relegated them to genteel sociability and working to encourage the men and children in their lives towards moral behavior. So these women were placed in a bind: On one hand, they were told to refrain from menial tasks in order to concentrate on the moral uplift of their families. On the other hand, they were criticized for lacking the strength and self-reliance of their ancestors. Despite being an era that saw tremendous advances in other areas, for middle-class women, the world grew more constricted. Rather than being working partners who contributed to their family’s economic well-being, respectable women were expected to be ornamental rather than productive. Only a few radical activists espoused the idea that women should be equal to men. Mary Baker Eddy did not advocate for social upheaval – her radicalism was limited to her absolute reliance on the power of God.11 In spite of the era’s inequalities, she did however take a different stance when it came to the movement she founded. She expected her Christian Science followers – both male and female—to work together as equals in advancing the Cause.12

Ushering in a scientific age

There is evidence that the earliest devices that used rotating wheels to spin natural fibers into thread or yarn were developed in China at least a thousand years ago. The design for the Baker family spinning wheel originated in Europe around 1300 AD. This invention enabled spinners to substantially increase their productivity over the simple hand-wound drop spindles that date back to biblical times. In addition to the large woolen wheels, a smaller spinning wheel for processing flax fibers into linen thread was invented around the same time.13 The revolutionary impact of the introduction of the flax spinning wheel is often under-appreciated. When textiles became less expensive and more readily available, people were much more willing to throw away worn-out or unfashionable clothing. Discarded linen rags then became a vital feedstock for paper manufacturing. This new supply of paper, along with Gutenberg’s printing press, facilitated both the Protestant Reformation – with its emphasis on the importance of each Christian reading the Scriptures for themselves – and the exchange of information and ideas that were vital to the Scientific Revolution.14

In her Message to The Mother Church for 1900, Mary Baker Eddy wrote, “The song of Christian Science is, ‘Work—work—work—watch and pray.’”15 These words, along those that follow in which she describes and compares “the right thinker and worker, the idler, and the intermediate,” reflect to some degree the New England in which she was raised, an era that emphasized the sturdy self-reliance and industrious labor so eloquently symbolized by her grandmother’s humble spinning wheel.

Timothy C. Leech received his PhD in Early American History from Ohio State University in 2017. He is a Public Historian and a former employee of both Longyear Museum and the Mary Baker Eddy Library. He and his family currently live in Ontario, Canada.