“The farm-house, situated on the summit of a hill, commanded a broad picturesque view of the Merrimac River and the undulating lands of three townships,” writes Mary Baker Eddy, describing the Baker homestead in Bow, New Hampshire, where she lived until she was 14. She adds: “But change has been busy.”1

And change was busy! In 1907, McClure’s Magazine launched a series of articles hostile to Christian Science and Mary Baker Eddy. The first installment included a picture of Mrs. Eddy’s birthplace taken in the early 1900s, after the house had been moved from its original location and was being used as a barn. Although admitting that the house was in “a sad state of disrepair,” the magazine also disparagingly described it as “a small, square box building of rudimentary architecture….”2

A strikingly different depiction of the Baker homestead has also come down to us. It is an etching by Mrs. Eddy’s cousin Rufus Baker, made under her direction in 1899.3 In addition to the well-kept appearance shown in the etching, we notice that the house was originally a saltbox. By the time the photograph was taken, the house had been remodeled, the saltbox had “lost its savour,” and the structure no longer accurately depicted the house Mrs. Eddy had once known.

But what evidence do we have beyond these two contradictory images? The house itself is no longer standing, and even if it were, by 1900 it had been radically altered. So we cannot appeal to the structure itself to settle the question.

The same magazine article also published an image of Mrs. Eddy’s home in North Groton, where she lived from 1855 to 1860, when she was Mrs. Patterson (below). While living here, she continued her study of the Bible and of homeopathy, gaining insights that were preparing her for her discovery of Christian Science.

By the time the photograph was taken, the former Patterson home was in a dilapidated condition. But it suited the tone of the McClure’s articles just fine: the magazine was doing its utmost in words and images to present a distorted portrayal of Mary Baker Eddy and her life.

Fortunately, this house has been preserved, researched, and maintained.

If Longyear Museum had not preserved this house, the photograph in McClure’s Magazine might be the only surviving evidence of its appearance. There would be nothing to check it against. And any research into evidence of structural changes or original painting schemes would have been irretrievably lost. The black-and-white image of a dreary and rundown house would be the only evidence of Mrs. Eddy’s surroundings during a period in which she was moving step by tentative step through bitter experiences and despair to catch shining glimpses of Christian Science. Surely an image that distorts should not be the sole evidence of her home during this period that witnessed the first gradual dawning of her discovery.

Historian Robert Peel has observed that “nearly every extensive published attack on Christian Science would start with a pejorative account of Mrs. Eddy’s life and character as the basis for its subsequent interpretation of Christian Science doctrine and practice.”4 This is graphically visible in the McClure’s depictions.

William W. Moss, who served for ten years as director of the Smithsonian Institution Archives, stated in his 1993 annual report:

Archives, museums, and libraries are institutions intentionally created by people to preserve material things we believe are of lasting value…. We know that nothing material is permanent…. We also know that in the modern world, information is plentiful…. In such a world, why do we need archives, libraries, and museums? … The answer is “so we may not be misled by fakes.” … It is socially necessary and probably psychologically essential that we prevent others from fooling us about the past. If all history is inevitably interpretation, it is best that we have the most reliable and most durable interpretation available…. We need durable evidence, evidence that survives over time, through changes in interpretation, to give us confidence in the information we use so freely…. [Archives, libraries, and museums] are places … for a “reality check” in a world of plentiful, competing, and sometimes contradictory information.5

The Longyear Museum collections—including paper documents, photographs, art, and artifacts, ranging from the smallest tintype photograph to the largest house—serve as “reality checks,” where people can have access to reliable evidence.

I have no doubt that people in future centuries, even those who are not Christian Scientists, will at the least recognize Mary Baker Eddy as a great religious reformer. We have the opportunity and the responsibility to preserve accurate evidence regarding her life and work for those future generations, so that they will not be misled by fakes.

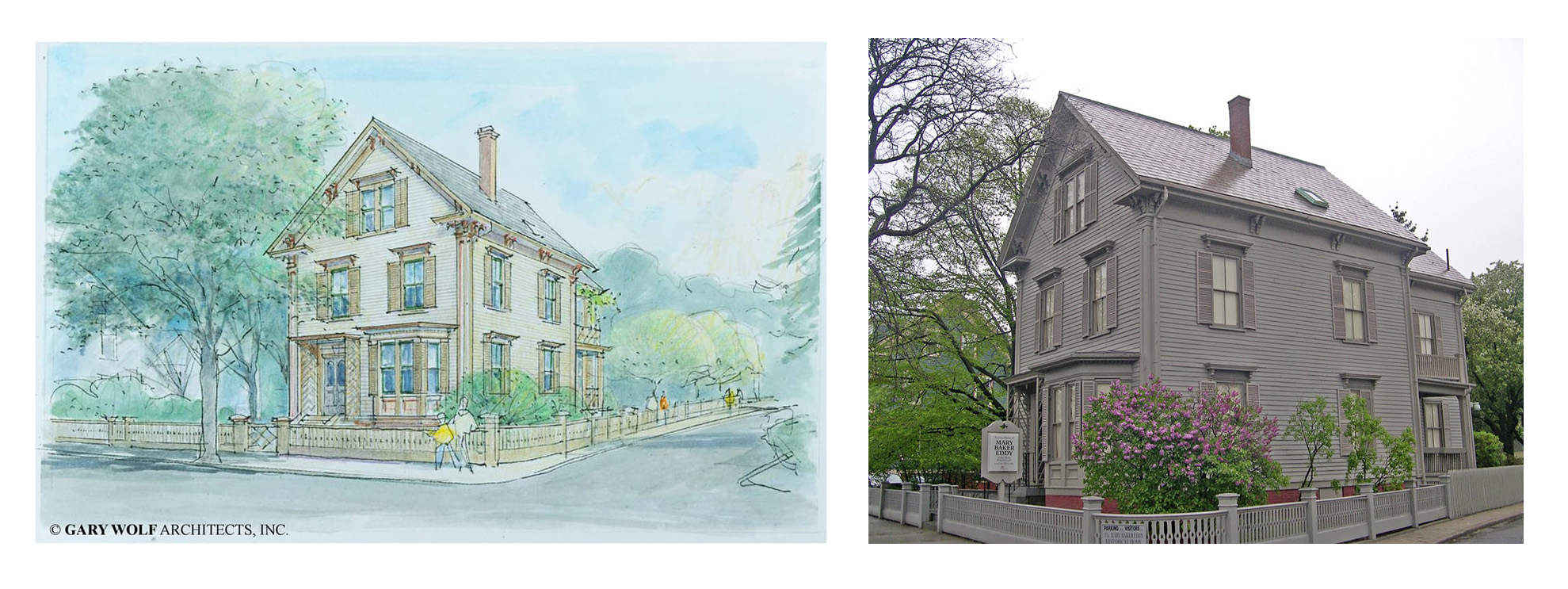

Recent research at the houses in Lynn and Chestnut Hill has led to reassessments of long-held assumptions and beliefs about Mrs. Eddy’s life there. Take Lynn, for example.

The house has been repainted many times since Mrs. Eddy moved from it in 1882. Over the years tastes changed, styles came and went, and its original color scheme was forgotten. Eventually it was painted gray. It has been gray for so long, that people assume it was gray when Mrs. Eddy purchased it in 1875.

But the evidence tells a much different story. This was no dreary, gray house where a lone woman with a mission might shelter down and regroup until her fortunes improved. This house had boldness and life. It suited this lone woman who also had boldness and life and was willing to confront a world, to step up out of boarding houses in order to finish her book, Science and Health, even if it meant having to step up into the attic to make ends meet.

Similarly, research at her former home in Chestnut Hill has revealed that the interior was radically altered to resemble the layout of Pleasant View, Mrs. Eddy’s home in Concord, New Hampshire, from 1892 to 1908. Pleasant View may no longer be standing, but its layout was largely reconstituted in the interior of Chestnut Hill.

This modification of the interior of a once-richer looking mansion to more closely resemble a farmhouse tells us that Mrs. Eddy lived up to her ideals.

She may have needed a large structure to accommodate her staff and to lead the Christian Science movement, but she deliberately chose to live simply in a suite of four rooms. It suited her ethic of hard work. It suited her life devoted to things of the Spirit. It suited her.

Research at the historic sites has been painstaking, exacting work. But as the well-known educator Edith Hamilton observes:

It is not hard work which is dreary; it is superficial work.6

The hard work at the houses has not been dreary. It has been anything but superficial. It has gone beneath the surface and revealed evidence unknown for a century. The work has brought new insight, understandings, and clarifications regarding the manner of Mrs. Eddy’s life.

We cannot predict what questions future generations will ask concerning Mrs. Eddy’s life, what distortions and fakes they may have to confront and refute. But it is our privilege to preserve for anyone interested in the truth the evidence that has come down to us.