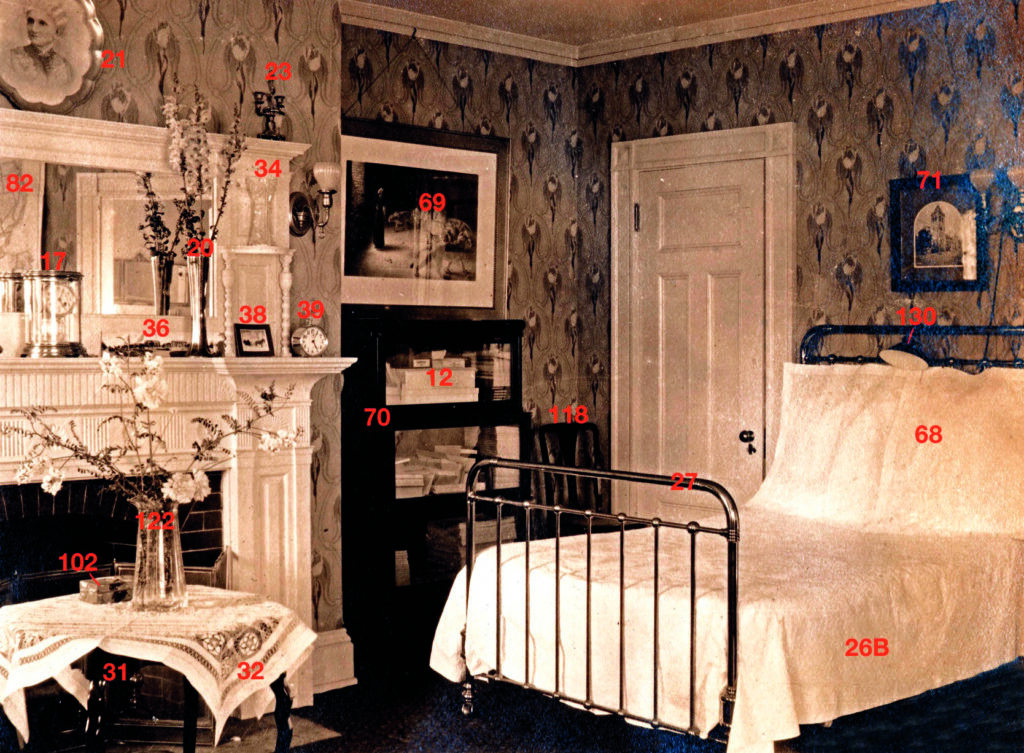

“I was taken to the room which was to be mine, directly over the library at the front of the house and on the same floor with the rooms occupied by our Leader. I found it equipped as an office as well as a bedroom. … The room was large, light, airy, and well furnished. … There were numerous letters on the desk from various places. …”

—Adam Dickey

Secretary and metaphysical worker at 400 Beacon Street, Chestnut Hill1

Today, 117 years after Adam Dickey first walked into the space that was to be his home (and office) for the next three years, visitors have an opportunity to form their own first impressions of the room—and gain a vivid sense of what it was like to live and work in Mary Baker Eddy’s household.

Through research and thoughtfully curated presentation of artifacts, Longyear Museum seeks to convey the stories of the people who served at 400 Beacon Street, and the significance of the work that was accomplished here. Such an interpretive approach, used by museums around the world, goes beyond dates and facts and “… can bring history and ideas to life, and enable visitors to engage with objects, people, and places from the past,” as one British curator and museum consultant writes.2

Whether one steps into Mrs. Eddy’s study, the rooms of Mr. Dickey or her other aides, or communal spaces such as the kitchen or parlors, each of the 28 period rooms at 400 Beacon Street is intended to contribute nuance and new insights into the remarkable history of this most remarkable woman.

Sources for Interpretation

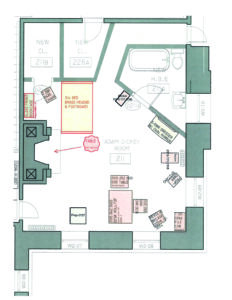

In addition to written reminiscences of household staff, Longyear used two sets of visual references as the basis for accurate restoration and interpretation: a rich trove of historic photographs (thanks to the many camera buffs in Mrs. Eddy’s household); and the 1907 blueprints for the renovation and expansion of the original 1880s building (which was nearly doubled in size to accommodate Mrs. Eddy’s staff).

Both proved invaluable, as the only areas containing any original furniture were the public rooms on the first floor (parlors, dining room, and library) and Mrs. Eddy’s suite on the second floor. Many of the rooms—those occupied by her staff, as well as the kitchen, pantry, and other workspaces—had been closed off and used for storage for decades.

Referring to these areas, design consultant Patricia Ford notes, “We faced mostly empty rooms … nothing that embodied the home that Mary Baker Eddy and her staff lived and worked in.” Confronting such a blank canvas provided both opportunities and challenges.

For instance, the layout of Mr. Dickey’s room had been substantially changed in the early 1950s, when The Mother Church owned the house. Original partitioning for the entryway, bathroom, and closet was removed to create a squared-off exhibit space. But historic photographs showed what the room originally looked like—and even provided a glimpse into the bathroom. Armed with this sliver of evidence, the 1907 blueprints, and markings later found on floorboards and in ceiling trim, the Longyear team was able to recreate the room’s original layout. This included the bathroom, now replete with details large and small—ranging from a clawfoot tub found in the basement to a period shaving mug, razor, and brush purchased at a local antique shop.

Interpretation Goals

The original aim had been “to represent exactly what each room looked like, per the photographs,” says Collections Manager Leslie Vollnogle. “But photographs taken at various points in time showed different interior arrangements,” so the approach was modified. Mr. Dickey’s room, for example, is interpreted based on a compilation of images and perspectives, with artifacts arranged to also allow for the smooth flow of visitors.

A core team of Longyear staff—including Leslie, Historic House Manager Rex Nelles, and Pam Partridge, director of education and historic houses—devised systems and tools to track and trace furnishing and interpretation needs for each of the 28 rooms.

One constant throughout the process was a commitment to providing an informative, authentic, and welcoming experience for visitors. As Rex puts it, “The idea is to have the rooms look as they were described—cared for, homey, and a place that people were happy to live in.” They’re arranged to evoke a sense of time and place, as if “the occupant has just stepped out—for a meeting, perhaps a meal—and will shortly return to pick up their tasks again,” he says.

Longyear’s hope is that visitors will leave 400 Beacon Street with an understanding and appreciation of how it supported home and family life for Mrs. Eddy’s household—while also serving as a hub of far-reaching activity and achievement in the early Christian Science movement.

Restoration and Interpretation: A Step-by-Step Process

Longyear staff followed a similar process for restoring and interpreting most rooms in the house. Close examination of historic photos allowed the team to:

- Identify each room’s three main design elements—flooring (carpet patterns), walls and windows (including wallpaper design and window treatments), and lighting (the placement, number, and type of fixtures). Preserved scraps of carpet and wallpaper discovered in unlikely places and computerized color-matching technology helped the team determine original colors and supported accurate replication by expert artisans.

- Inventory the contents of each room as shown in the period photographs and compare that list with items currently in Longyear’s collection. Furniture original to the house was sent out for reupholstering. Appropriate period pieces in Longyear’s collection were prepared in-house—including minor repairs, staining, polishing, and the like. To locate major items seen in the historic photos but not in the collection, the team visited online antiques purveyors as well as in-person fairs and sales.

- Make final interpretation decisions on positioning of furniture, decorative objects, and artwork in order to engagingly convey the story of that room and its occupant or function, while also making it easy for groups of visitors to move through the space.