Mary Baker Eddy’s life immediately following her discovery of Christian Science in 1866 found her largely bereft of human aid, home, and support. But Mrs. Eddy described what took place during these years in very different terms. “The search was sweet, calm, and buoyant with hope, not selfish nor depressing,” she later wrote in Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures.1 Though not without challenges, her days were filled with searching the Bible, putting her findings into writing, teaching students, and healing—all laying the foundations for her future work to establish Christian Science. One place she found refuge during these transitional and formative years was in Amesbury, Massachusetts.

A Quiet Respite

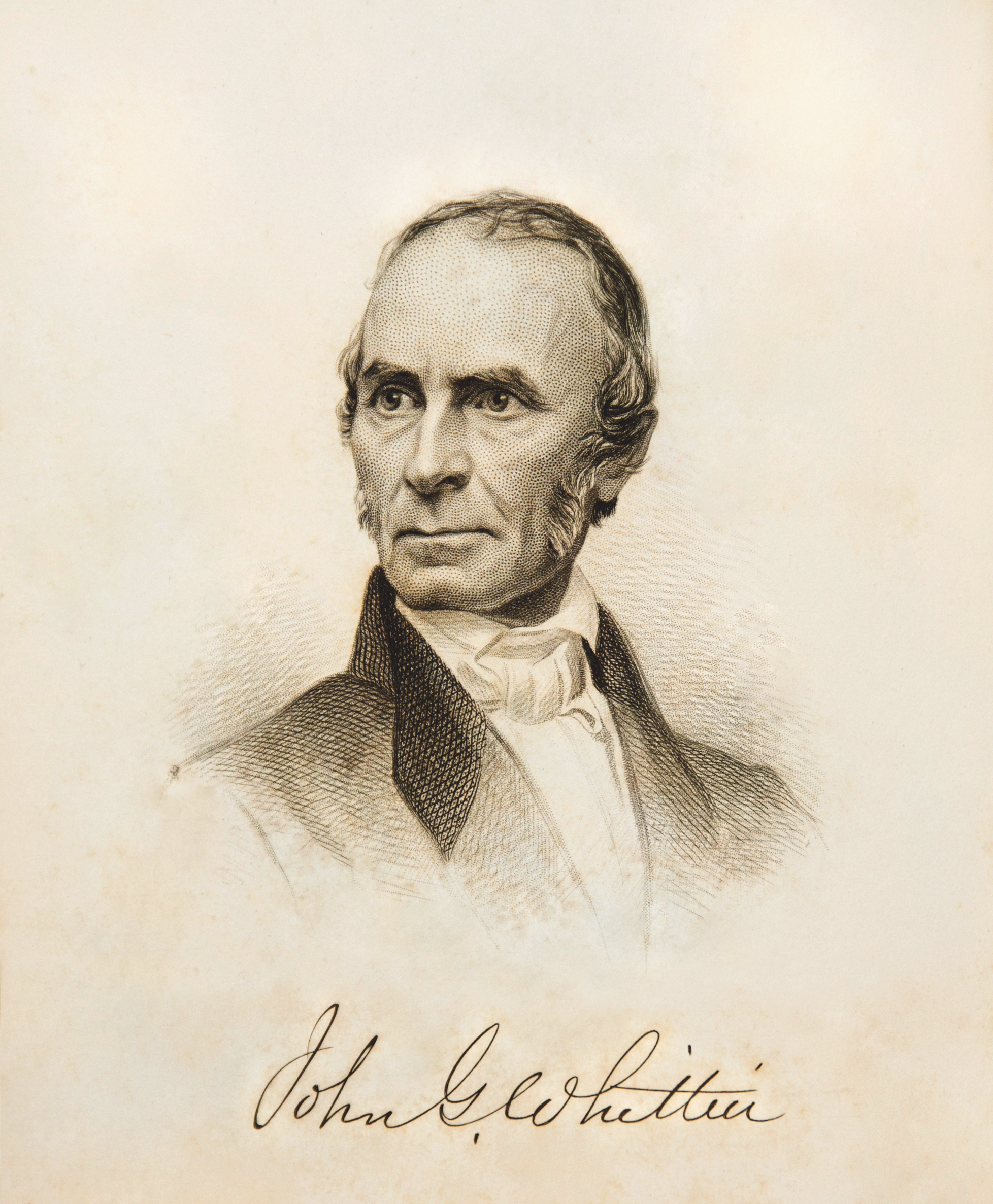

The quiet town of Amesbury, home to poet John Greenleaf Whittier, lies sandwiched between the New Hampshire border and the placid Merrimack River. Mrs. Eddy first ventured there in the autumn of 1867, at the suggestion of friends who knew she was in search of a peaceful place to study and write.2 The previous year had been a momentous one for her. In February, she had experienced a transformative healing after a severe fall on icy pavement, through spiritual means alone.3 Two months later, she was deserted by her second husband and, struggling to make ends meet, moved several times before arriving in Amesbury. (At the time, she was known as Mrs. Patterson, but soon resumed use of her name from her previous marriage, Mrs. Glover.)

For 10 months, she rented a room in a home owned by a retired sea captain and his wife.4 But that sojourn came to an abrupt end when her hosts’ son cleared the house of boarders in preparation for his summer vacation, putting Mrs. Eddy and her trunk out on a rainy night. Sarah Bagley, who lived not far away on Main Street, offered her a spare second-floor bedroom in June and July 1868. Later, after a year-and-a-half stay in Stoughton, Massachusetts, Mrs. Eddy would return to Miss Bagley’s house in the spring of 1870.5

Mrs. Eddy later recounted that she spent these formative years seeking to know how her healing had happened—and to understand the divine laws that brought it about. “For three years after my discovery,” she wrote of this period in Science and Health, “I sought the solution of this problem of Mind-healing, searched the Scriptures and read little else, kept aloof from society, and devoted time and energies to discovering a positive rule.”6 She added, “I won my way to absolute conclusions through divine revelation, reason, and demonstration.”7 She was also quietly pondering her mission.8

Writing

Amesbury provided a place where Mrs. Eddy could put on paper what she was learning from her prayerful search.

“Writing, writing, writing, she was always writing, the sheets falling to the floor beside her,” an acquaintance observed. “She seldom went out, she saw few people; she simply sat and wrote.” 9

Mrs. Eddy made hundreds of pages of notes full of spiritual interpretation of the Scriptures during this time. “In following these leadings of scientific revelation,” she explained, “the Bible was my only textbook. The Scriptures were illumined; . . .”10 Despite their rudimentary nature, she cherished these exploratory writings. “These early comments are valuable to me as waymarks of progress, which I would not have effaced.”11

Mrs. Eddy’s comments on the Bible, including on the book of Genesis, “laid the foundation of my work called Science and Health,” she added.12 When the sixth edition was published in 1883, it included for the first time a glossary of biblical terms in a new section titled Key to the Scriptures. A number of the definitions can be traced to her scriptural notes from this period.13

Teaching

Shortly after arriving at Miss Bagley’s, Mrs. Eddy took out an advertisement in the Banner of Light. The Boston weekly’s editor was a native of Amesbury, and historical evidence shows that he and Mrs. Eddy crossed paths at least once at a gathering with local literati. This spiritualist newspaper was, perhaps, a place where unconventional thinkers might be reached, though her ad clearly distinguishes her discovery from spiritualism. As one of her students later explained, “When she was asked why so many of her early converts and early friends were among Spiritualists, she replied: ‘Because they were liberal, kind-hearted people, and were quite ready to accept new ideas.’”14

That ad, placed in the July 4, 1868, issue, read: “Any person desiring to learn how to heal the sick can receive of the undersigned instruction that will enable them to commence healing on a principle of science with a success far beyond any of the present modes. . . .” The conclusion underscored Mrs. Eddy’s confidence in what she was discovering and her ability to impart it to others: “No pay required unless this skill is obtained.”

Mrs. Eddy had taught her first student in early 1867, but after a year and a half of steadily gaining clearer glimpses of her discovery, the time was ripe for further teaching. One of the individuals who answered the call was Sarah Bagley herself.15

One manuscript that Mrs. Eddy worked on during this period was The Science of Man. Copyrighted in 1870, this teaching manual was filled with questions and answers and, like her notes on the spiritual interpretation of the Bible, also laid the foundation for a future chapter in Science and Health: “Recapitulation,” which was introduced in the third edition in 1881.16

Healing

Throughout these years, Mary Baker Eddy carried on her healing work. “I am torn asunder almost by requests to heal the sick and somehow they keep me at it continually,” she wrote Miss Bagley in 1868.17 John Greenleaf Whittier, who lived just down the street from the Bagley home, was one who was healed—of what Mrs. Eddy later described as “incipient pulmonary consumption.”18 Visiting him, she found him coughing and unable to talk above a whisper. Speaking to him “in the line of Science,” she soon noticed a shift: “By and by his countenance changed and the sunshine of his former character beamed through the cloud….” Before she left, he told her, “I thank you Mary for your call, it has done me much good.”19 Other healings recorded during this period include a mentally ill man who had escaped from a psychiatric hospital and a woman suffering from pneumonia.20

During a period in her life that outwardly appeared transitory and largely bereft of human support, Mary Baker Eddy’s resolute inward search for God went on unencumbered. Through writing, teaching, and healing, her time in Amesbury helped pave the way for the forward movement of Christian Science.

Kelly Byquist is a research associate at Longyear Museum.