Click, clack.

Click, clack.

Slide, br-r-r-ing, repeat.

(And, while you’re at it, don’t forget the carbon paper!)

While typewriters—both manual and electronic—are now a relic of workplace history, their legacy lives on in modern-day devices such as the English-language QWERTY keyboard layout as well as the term “backspace,” for example.1 When the first U.S. patent for a typewriter was granted to inventor Charles Sholes on June 23, 1868, the machine was considered a marvel of its time.2 (That date now marks “National Typewriter Day” in the United States).

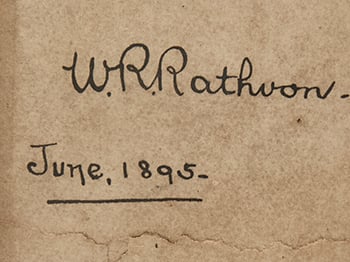

Staff supporting the work of the Discoverer, Founder, and Leader of Christian Science were already making use of typewriters by the 1880s.3 Mary Baker Eddy was a prolific writer—of religious texts and regular correspondence, of prose and poetry—and set down her thoughts and ideas in longhand or dictated shorter missives to her staff. In those early years of typewriting technology, her longest-serving aide, Calvin Frye “taught himself how to use the typewriter so that he was able to type many of his letters, though not very skillfully,” recalls Rev. Irving Tomlinson, a fellow staff member.4

Soon, across the United States, typewriters became indispensable to economic productivity and the functioning of factories, offices, and government departments.5 Leaders and managers in the private and public sector came to appreciate the speed, readability, and quantity of output (through improved carbon paper).

By the time Adam Dickey joined Mrs. Eddy’s Chestnut Hill household in early 1908 (a few weeks after her move from Concord, New Hampshire), Tomlinson notes, “She was greatly in need of added secretarial assistance … . There was no one in the family who could handle a typewriter very efficiently,” resulting in a considerable backlog of correspondence.6 Tomlinson continues, “… as he [Dickey] was a rapid typist he proved to be a handy man for Mrs. Eddy to have in the home” and immediately took over as associate secretary.7

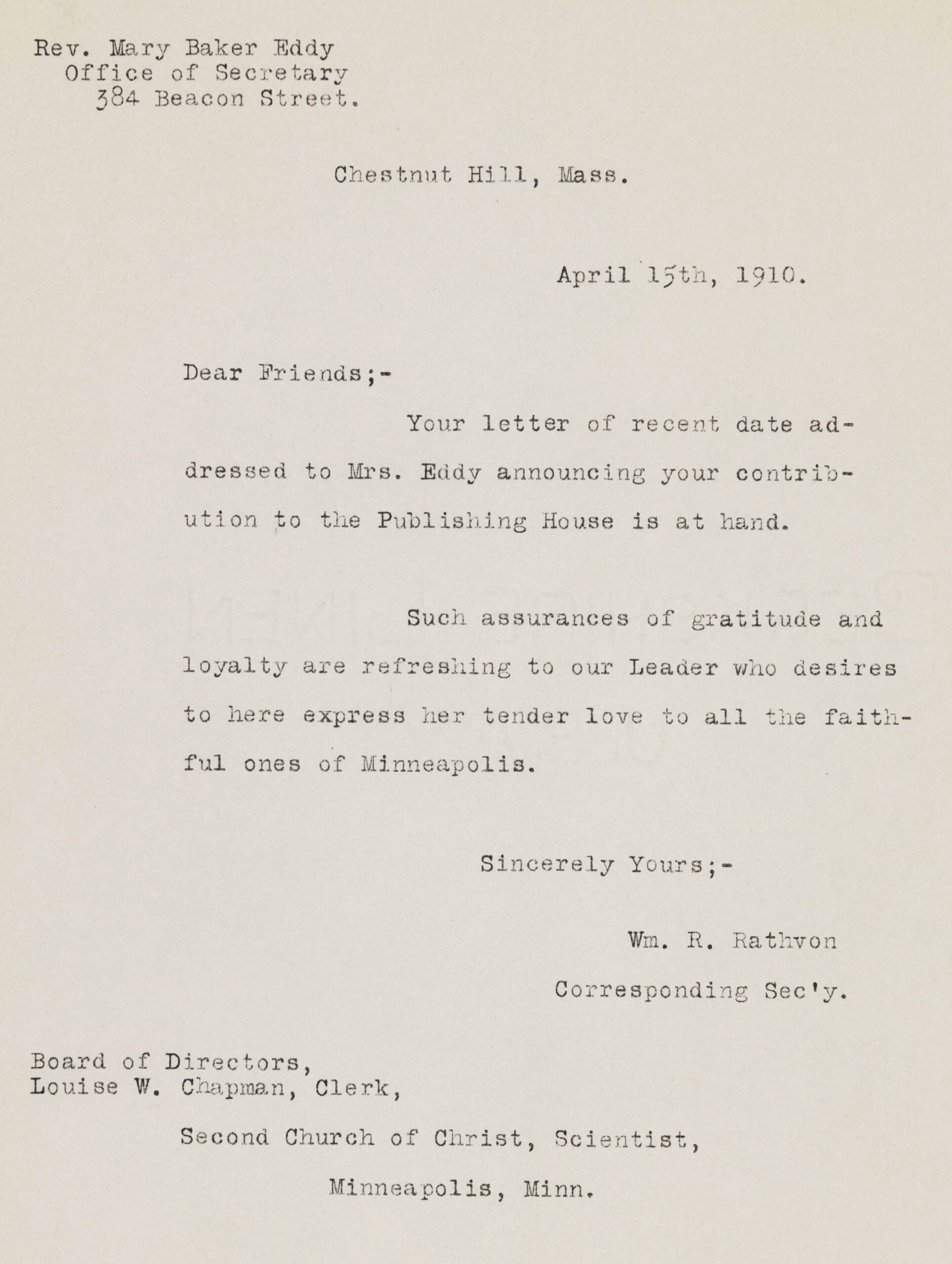

Mr. Dickey, along with Calvin Frye, Irving Tomlinson, and William Rathvon who joined a few months later, constituted the team that handled Mrs. Eddy’s communications with various parties—including officials of her Church and of the Christian Science Publishing Society, members of the press and the clergy, and, of course, her own students and followers of Christian Science.8 To support their work, the secretaries were equipped with quality typewriter models of the time. This work went on at all hours of day—and, according to at least one reminiscence, also at night.9

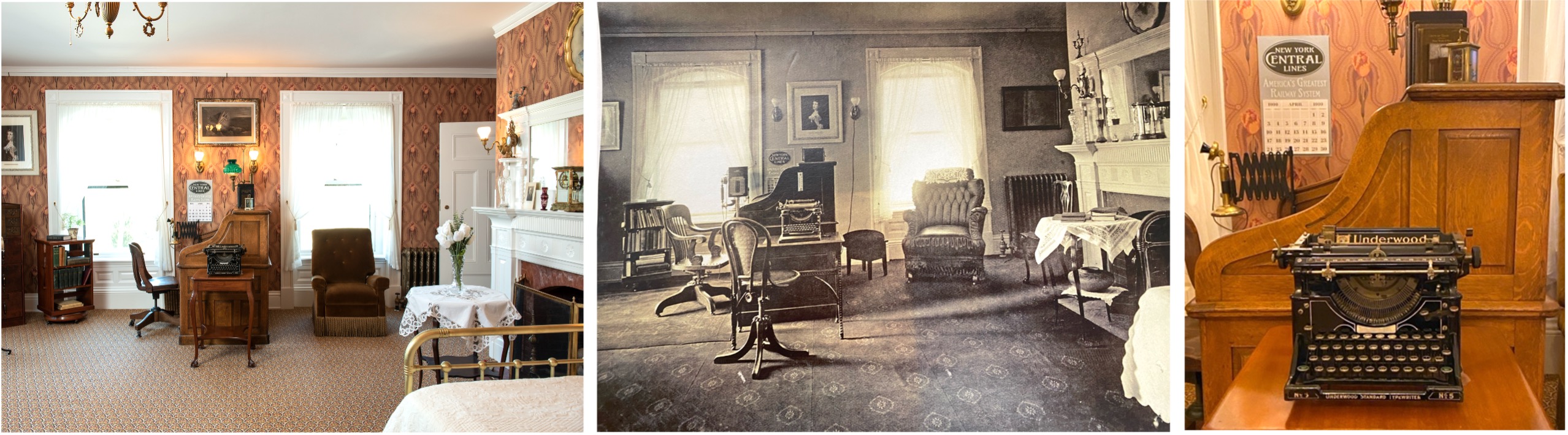

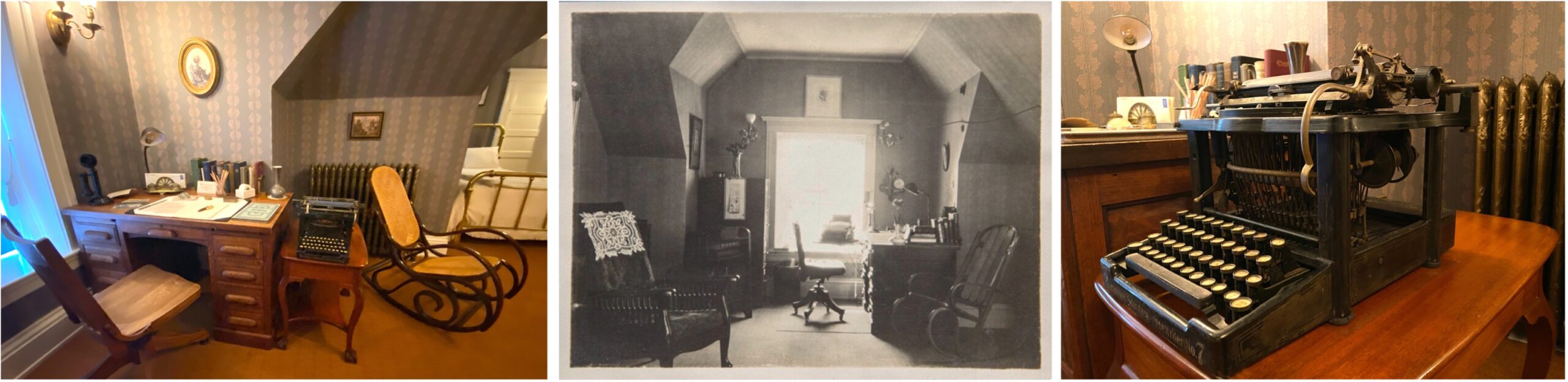

While Longyear Museum does not have in its possession the original typewriters used at 400 Beacon Street, we have been able to locate period machines that are very close in style and form to those depicted in historic photos. Visitors to the newly restored Mary Baker Eddy Historic House in Chestnut Hill will be able to view these sturdy machines—some of them weighing more than 20 lbs!—in the interpreted rooms where secretaries Dickey, Frye, and Rathvon lived and worked.

As you walk into those rooms—either in person, or virtually, through the photo galleries below—you may just be able to imagine the picking and pecking of keys, the clicking and clacking of those machines, as Mrs. Eddy’s staff assiduously and accurately documented her thoughts, directives, and other messages for posterity.

Adam Dickey’s room

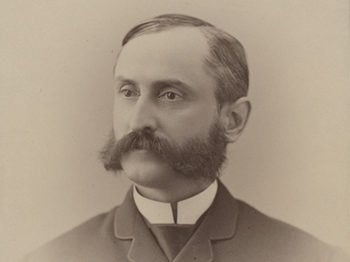

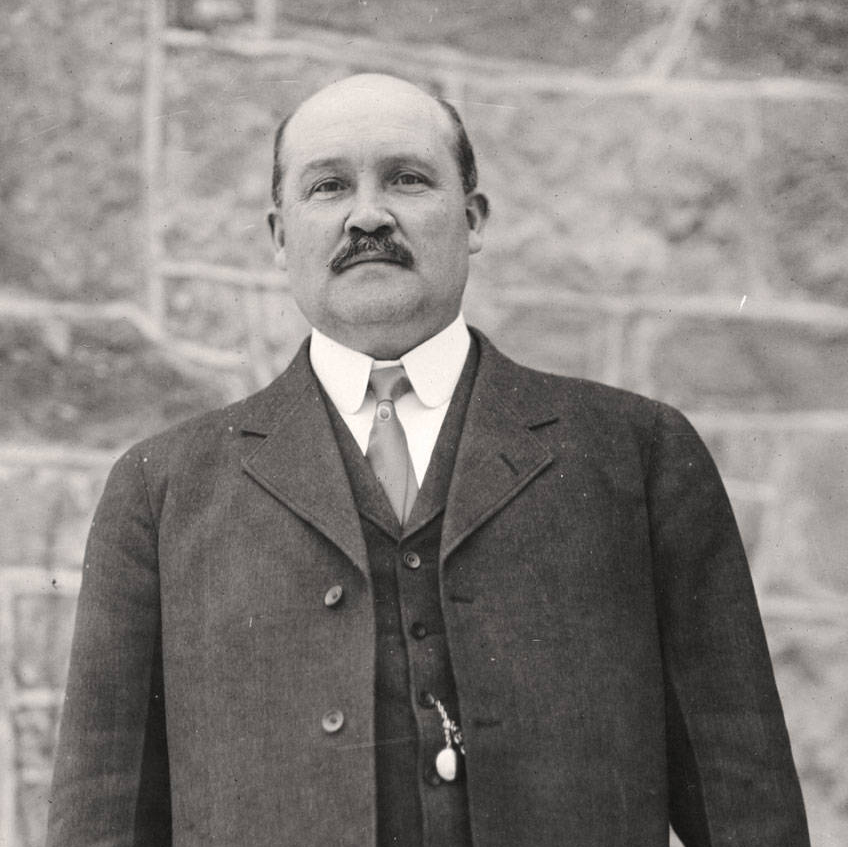

Arriving at Chestnut Hill from Kansas City in February 1908, Christian Science practitioner and teacher Adam Dickey contributed essential metaphysical support in the household—as well as welcome typing skills and speed!

Arriving at Chestnut Hill from Kansas City in February 1908, Christian Science practitioner and teacher Adam Dickey contributed essential metaphysical support in the household—as well as welcome typing skills and speed!

His room is arranged and interpreted almost exactly as depicted in historic photos in Longyear’s possession—including the placement of a typewriter on a little table next to his desk, which was well lit by two large windows. (The machine in his room today is a black metal Underwood Standard Typewriter No.5, dating to 1917.)

Calvin Frye’s Room

Calvin Frye’s Room

During his 28 years working for Mrs. Eddy, Calvin Frye fulfilled multiple roles—bookkeeper, household manager, metaphysical support, secretary, confidante. Though typing may not have been his forte, Mr. Frye had other strong points that Mrs. Eddy greatly prized, especially his honesty and loyalty.

In this historic photo of Mr. Frye seated at his mahogany rolltop desk, you can glimpse his typewriter on its ingenious swivel stand, behind him. And, if you visit 400 Beacon Street, you’ll see the desk (a gift to mark his faithful service) and stand in their original location.

While the whereabouts of Mr. Frye’s original typewriter are not known, we have a very close replica, a Hammond #2, dating from 1899. Longyear sourced this rare semi-circular machine, complete with its wooden cover, from a collector in the Netherlands. (When he heard that it would be displayed in a museum, he offered a generous 50 percent discount and even paid for the shipping!)

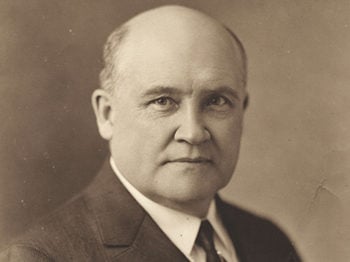

William Rathvon’s room

William Rathvon’s room

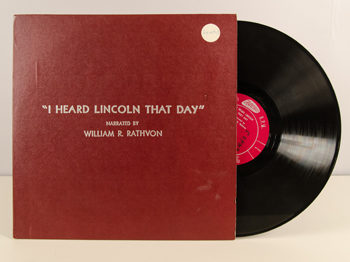

Hailing from Colorado, Christian Science practitioner and teacher William Rathvon was called to serve Mrs. Eddy as a corresponding secretary and metaphysical worker in 1908. His room has also been restored and interpreted to give a sense of his role on staff as well as his interests (which included birdwatching and photography).

A historic photo shows Mr. Rathvon’s typewriter placed on the windowsill beside his desk. In his restored room today, a period Remington Standard Typewriter #7 (a model manufactured from the late 1890s to the early 1900s) sits on a little side table to the right of the desk.