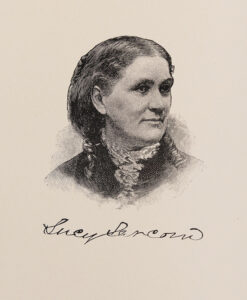

Lucy Larcom

Teacher and poet Lucy Larcom was born in 1824, just three years after Mrs. Eddy. She found poetry all around her.

“To me, the reverent faith of the people I lived among, and their faithful everyday living, was poetry; blossoms and trees and blue skies were poetry,” she wrote in her memoir, A New England Girlhood. “The highest possible poetic conception is that of a life consecrated to a noble ideal.”1

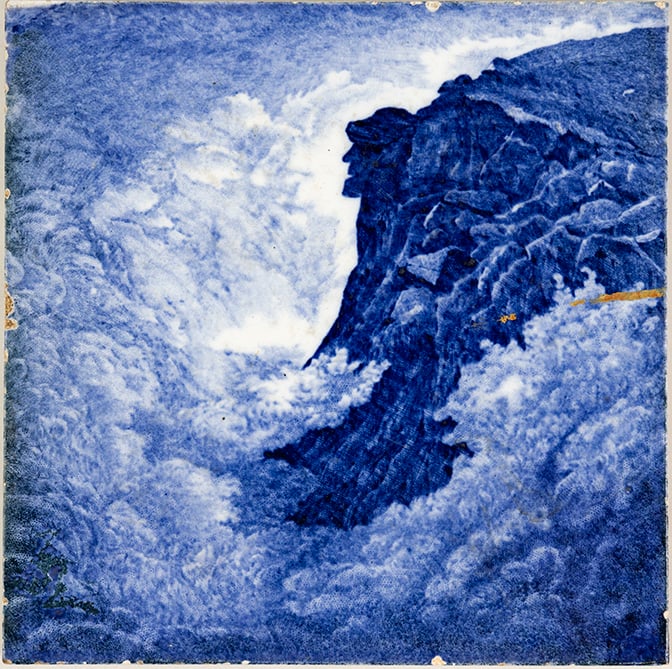

Like Mrs. Eddy, Miss Larcom visited the White Mountains. Her 1869 collection, Poems, included “My Mountain,” which mentions the famous rocky outcropping and describes the scenery around Franconia Notch, including the Pemigewasset River. One portion reads:

’Tis the musical Pemigewasset,

That sings to the hemlock-trees

Of the pines on the Profile Mountain,

Of the stony Face that sees,

Far down in the vast rock-hollows

The waterfall of the Flume,

The blithe cascade of the Basin,

And the deep Pool’s lonely gloom.2

Miss Larcom grew up in Beverly, Massachusetts, and worked for a decade in the mills in Lowell, starting at age 11. One of her jobs was in a quieter room, where she was able to study, and at times she attended school. By about 14, she had become part of a literary circle with other mill girls and was publishing poems in their magazine.3

She later befriended poet John Greenleaf Whittier, with whom she visited New Hampshire. She dedicated her poetry book to his sister, Elizabeth.

Mrs. Eddy knew Mr. Whittier in Amesbury, Massachusetts, where she lived in 1868 and 1870, when she was healing, beginning to teach, and writing notes that would become the foundation of Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures. In fact, she healed the famous poet of what she later termed “pulmonary consumption” on her first visit to him.4

Mrs. Eddy and Miss Larcom, along with Mr. Whittier, attended a gathering together at one point during this time, although the depth of the two women’s acquaintance is unknown.5

The Christian Science periodicals included poems, verses, and short prose by Miss Larcom more than a dozen times between 1886 and 1927, most of them during Mrs. Eddy’s lifetime. Additionally, a 1904 newspaper clipping of her poem “Three Old Saws” was included in one of the scrapbooks kept by Mrs. Eddy and her secretary Calvin Frye. The poem, about how to overcome lack or sorrow by giving to and cheering others, was included in a long-running feature in the Boston Globe, “Poems You Ought to Know.”6

CLICK HERE to read the lead article in this compilation—which delves into Mrs. Eddy’s early versions of her poem, ‘Old Man of the Mountain,’ as well as her later revisions and its final publication in her book, Poems.

Moody Currier

“The sons and daughters of the Granite State are rich in signs and symbols, sermons in stones, refuge in mountains, and good universal,” Mrs. Eddy wrote in an 1898 message to the Christian Scientists who gathered in the summertime at a church in the White Mountains.7

Moody Currier was one of those sons. A newspaper editor in Manchester, New Hampshire, he served as the state’s governor from 1885 to 1887. He had also been a classmate of Mrs. Eddy’s brother Albert at Dartmouth College and a fellow member of Phi Beta Kappa.8

Mr. Currier published his poem “The Old Man of the Mountain” in 1906 in Granite State Magazine. It drew upon similar themes to the young Mary Baker’s.

The first lines read:

Thy home is on the mountain’s brow,

Where clouds hang thick and tempests blow.

Unnumbered years, with silent tread,

Have passed above thy rocky head;

Whilst round these heights the beating storm

Has worn, with rage, thy deathless form.

And yet thou sit’st, unmoved, alone,

Upon this ancient mountain home.9

Although Mrs. Eddy had been close with her brother Albert, who died in 1841, it’s not clear how well she knew Mr. Currier. He was not a Christian Scientist but wrote to her in August 1895 about receiving several volumes from her, concluding: “I wish to congratulate you upon the broad and independent foundation on which you are now building your great work and trust that your fame and renown may last as long as the principles you teach.”10

Mrs. Eddy was living at Pleasant View, her home in Concord, New Hampshire, at this point. In another letter that summer, after she sent Mr. Currier an additional book, he wrote back that it was full of wisdom. “God is eternal Life, in Him all things exist. On this truth all science, all religion must be founded,” he wrote, adding, “Mrs. Currier wishes to be very kindly remembered to you.”11 Mr. Currier’s “Old Man” poem is included in a book that his wife, Hannah Slade Currier, later gave to Mrs. Eddy—a posthumous compilation of his addresses and poems published in 1899.12