Christmas 1887 brought a flurry of activity to the Christian Scientists living in Boston.

For nearly a decade, ever since “a little band of earnest seekers after Truth” — students of Mary Baker Eddy’s and therefore members of the Christian Scientist Association — had voted in favor of her motion to form the Church of Christ, Scientist,1 worship services for the group had been held in rented halls. Now, they were eager for a church building of their own.

Raising money in support of a church edifice had begun in earnest around 1885.2 Various initiatives to support the project were announced in The Christian Science Journal, and financial gifts from the field began streaming in. In the summer of 1886, a committee acting for the church purchased a plot of land in an area of the city known as the Back Bay. In addition to the initial down payment of $2,000, the church committee took out a three-year mortgage for the remainder.3 Following this purchase, however, “means and methods for raising money to pay off the mortgage in the allotted time became the absorbing topic of interest to the members of the Church.”4

Socials, bazaars, and suppers were familiar fundraising avenues to those who had left mainstream churches of the day for Christian Science. At some point in the spring of 1887,5 the girls in Mary Eastaman’s Sunday School class had a bright idea. Why not hold a Christmas fair?

“They were but children, yet they possessed earnestness and zeal, and their faithful teacher encouraged them in the undertaking,” the Journal reported.6

Initially, the adults were skeptical. “We are a very busy people,” the official program for the event would eventually explain, “and the thought of a Fair at first seemed frivolous.”7 In the end, though, the enthusiasm of the Sunday School students proved irresistible. “Their zeal inspired their elders, and so the Scripture was fulfilled, ‘Out of the mouths of babes, Thou hast perfected praise,’” noted the Journal.8

Mrs. Eddy, however, wasn’t as enthusiastic, cautioning her flock in that summer’s communion service about the dangers of casting their nets on the wrong side. “This is the important thing to understand,” she would tell them. “Which is the right side? Is it the material or the spiritual side of life and its pursuits?”9

The congregation didn’t heed her thinly-veiled message — or didn’t connect it to their fund-raising plans — and proceeded undeterred. Mrs. Eddy agreed to let the event take place, apparently willing that the event should be an object lesson.10 A call went out to all readers of the Journal, requesting that any financial contributions or donated articles for the bazaar be sent to Boston.11

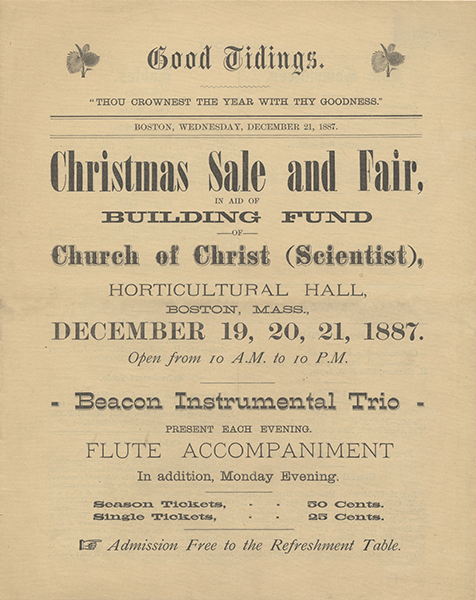

Billed as a “Christmas sale and fair,” the event was held in Boston’s old Horticultural Hall on the corner of Tremont and Bromfield Streets. It lasted three days, from Monday, December 19, through Wednesday the 21st.12 The doors opened at 10 am and didn’t close until 10 pm each night. It was a gala event, complete with live music, fresh flowers, and rugs and draperies on loan from local businesses “for decorative purposes,” which “enhanced the beauty of the goods and the appearance of the hall.”13

According to one account, “the hall was prettily decorated with fans, Japanese umbrellas, and embroideries. The eleven committees in charge provided for the refreshments, confectionery, flowers, needlework, and other commodities usually found at such bazaars.”14

A section of the space was set apart as a restaurant. In a review of the event afterward, the Journal proclaimed the food “excellent in quality,” including cake “gratuitously furnished by friends,” salad, beverages, and turkey (“unusually well roasted, one of the members sitting up over night to accomplish this feat for the feast”).15

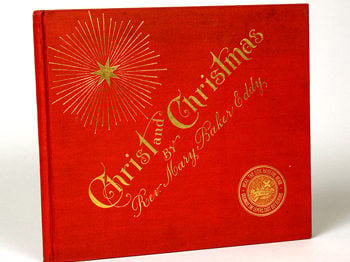

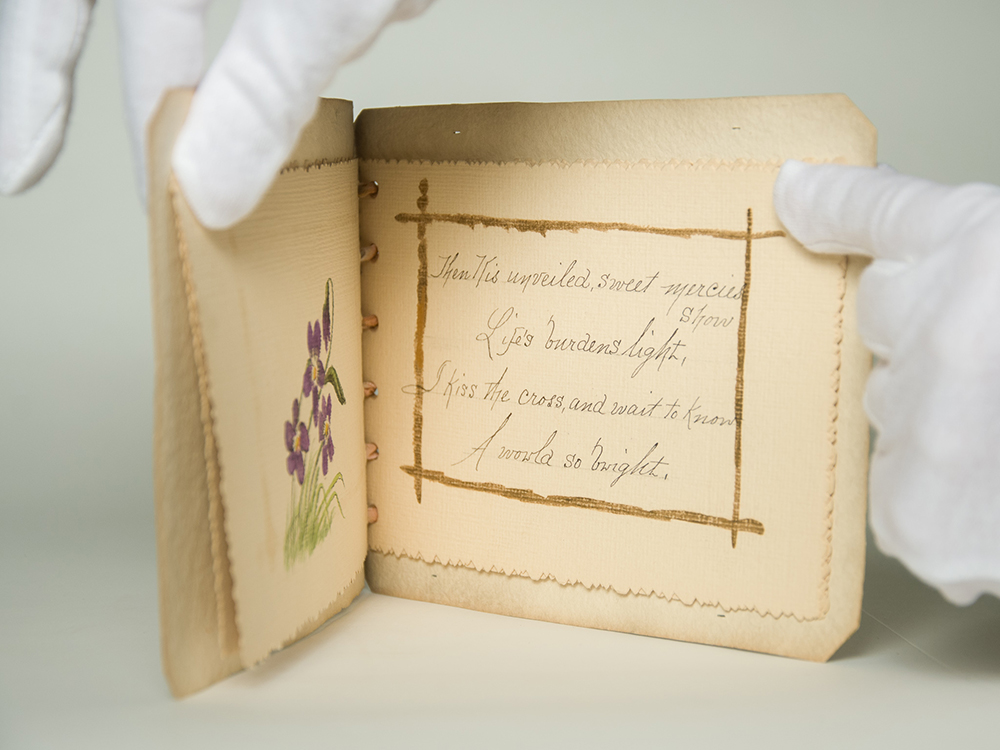

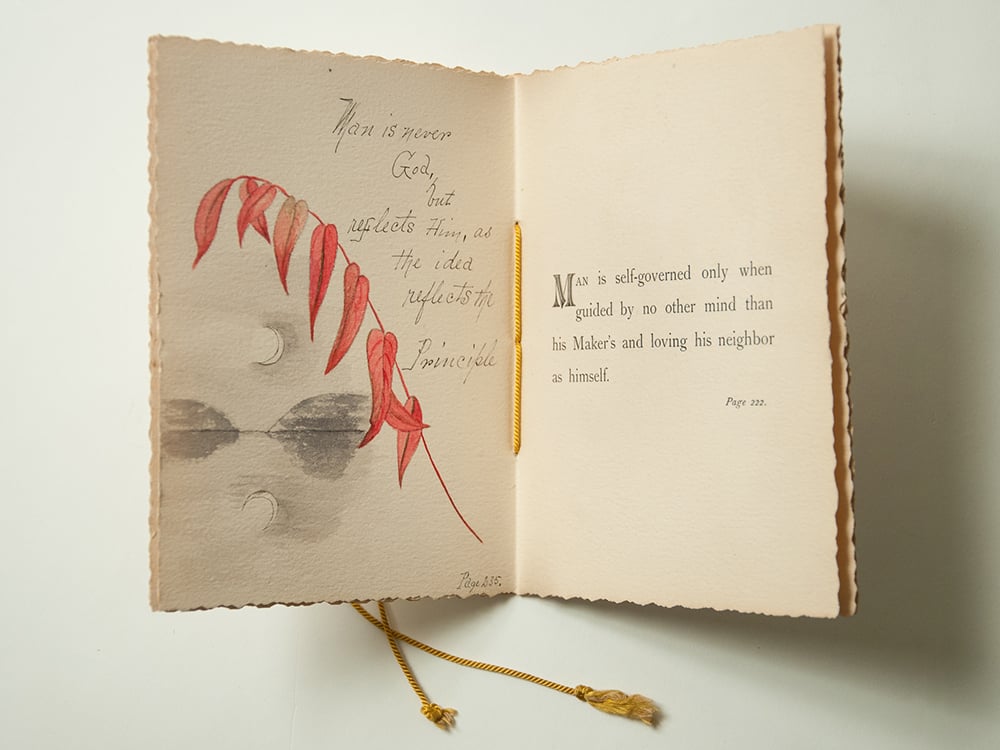

As for the offerings for sale, there was more food, including crackers, ears of popcorn, preserves, and candy. There was artwork, including paintings of all sorts, “on brass, porcelain, china, canvas, velvet, satin, silk.” There was bric-a-brac and needlework, from hand-painted and embroidered cushions to mantel-scarfs, tablecloths, and more.16 And there were books — some of them handmade.

Despite her misgivings, Mrs. Eddy attended the fair on Tuesday evening with her son and his family, who were in Boston visiting from their home in the Dakota Territory. Their presence caused a delighted stir.

“On the evening when our Leader was present, the hall was packed,” observed one report, “and happiness and good-fellowship prevailed.”17

The fair was remarkably successful in raising funds for the payment on the mortgage. “The net profits for the building-fund were piles of dollars and heaps of happiness,” enthused the Journal.18

Alas, that happiness would be short-lived. Several months later, William H. Bradley, the treasurer for the sale, absconded with the proceeds.19

Without the funds to pay off the mortgage, the church was facing a substantial loss, including its prime piece of real estate. Mrs. Eddy took action, stepping in to acquire legal control of the land in late 1888. She transferred the title first to Ira Knapp, and then to three trustees tasked with raising funds to build an edifice.20 In the summer and early fall of 1892, after the trustees tried to incorporate the Publishing Society into the construction project, creating a “Christian Science Headquarters,” Mrs. Eddy dissolved that trust and deeded the land to the Board of Directors, for the sole purpose of building and maintaining a church edifice.21

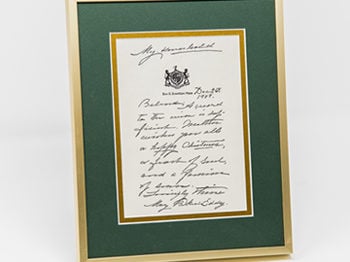

Explaining her actions — and perhaps offering a rebuke to the human ways and means behind such measures as the Christmas fair — she would write, “The lot of land which I donated I redeemed from under mortgage. The foundation on which our church was to be built had to be rescued from the grasp of legal power, and now it must be put back into the arms of Love, if we would not be found fighting against God…. The First Church of Christ, Scientist, our prayer in stone, will be the prophecy fulfilled, the monument upreared, of Christian Science.”22

Within two and a half years after these words were written and the idea was “put back into the arms of Love,” the building Mary Baker Eddy called “our prayer in stone” was constructed, and Christian Scientists finally had a church to call their own.