The first entry in Mary Baker’s “Journal of a trip to the White Hills in July 1843” describes a pelting rain and the “dull requiem” of a “lonely night-wind.”1 She was missing a special someone, but soon the rain would stop, and her cloudy outlook would yield to inspiration and hope—with a little assist from a stern old man.

Mary and her brother George had traveled about 35 miles north from their home in Sanbornton Bridge, New Hampshire, to Thornton that Monday, July 17.2 On Tuesday, the weather cleared as they went another 50 miles to Franconia Notch, a storied mountain pass at an elevation of nearly 2,000 feet through the White Mountains.

The mountain scenery prompted 22-year-old Mary to muse about looking down like a bird in flight “to contemplate all in God and God in all.” She depicted the giant hills “seen from their cloud-capped summits as if in communion with Heaven and reposing in the very arms of Deity.”3

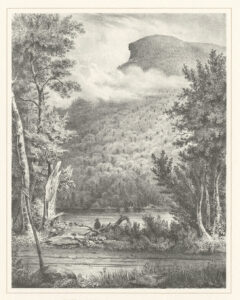

When the carriage stopped in Franconia Notch, she took a seat beside the road and looked up—to see a stone formation jutting out from nearby Profile Mountain that resembled a human face, an outcropping known as the “Old Man of the Mountain.”4

“I was lost in admiration when contemplating the ‘Old Man!’ so forcibly shadowing forth the symbols of an invisible power,”5 Mary would later note in a foreword to the poem she began writing right there on the side of the road. Some fellow tourists happened by and asked to hear it and have her send them copies, which she did.6

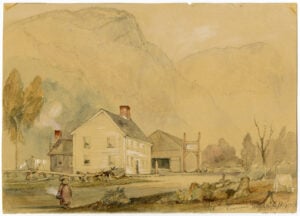

She spent that night in her “sleeping chamber at the ‘Notch house.’”7 This was most likely a farmhouse that had been set up in 1835 with a tavern for guests and a barn that could service carriage horses.8

Even though she was “too fatigued to write longer” in her journal, she had to “make honorable mention of the ‘Old Man of the Mountain.’ And a rock-bound sire he is, upon a ragged cliff beyond the reach of mortal! Stern and passionless, his rigid features betray no soul—tho they present from one point a complete profile of the human face.”9

In the first published version of her poem, she would refine that impression:

Stern,—passionless,—no soul thy looks betray;

Though kindred rocks, to sport at human clay—

Have traced thy features, like the sculptor’s skill,

With knowledge limited and reason frail.

Another stanza portrays the Old Man as lonely:

Great as thou art, and paralleled by none!

Admired by all—still thou art most forlorn:

The morn looks down upon thine exiled height;

The stars, so “wildly, spiritually bright,” 10

Mary herself appears to have felt “forlorn” at the beginning of the trip, presumably because, for some time, she had not received any letters from her suitor, George Washington Glover. Her father had been blocking the correspondence, but her brother had found a way around that by telling Mr. Glover to send Mary letters during the trip.11 The journey lasted at least a week, including several days during which Mary parted from her brother and visited friends. Her journal entries became more cheerful on Wednesday: “Never have I enjoyed a ride as much since I left home as the one this morning with Geo from Franconia to Littleton, and from thence to Haverhill alone,” she wrote that night.12

If the letters from Mr. Glover came through, they apparently had their intended effect: Mary married him in December that year and moved to South Carolina. While in the South, she first published her poem, “Old Man of the Mountain,” in July 1844 in The Floral Wreath, and Ladies’ Monthly Magazine, which was based in Charleston.

The rocky profile that inspired her poem was spotted by white settlers in 1805, during surveying work.13 To the indigenous Abenaki people, the “Stone Face,” as they called it, had long represented the main character in a mythical love story, watching over the lands protectively.14 An 1823 publication called A Gazetteer of the State of New-Hampshire described the stone formation as “a singular curiosity.”15

In the mid- to late-1800s, the White Mountains were among the most popular scenic destinations in the United States, thanks largely to the draw of the Old Man of the Mountain. Such well-known figures as Nathaniel Hawthorne and Daniel Webster paid homage to the face, which was eventually featured in the New Hampshire state emblem and on license plates and countless souvenir items. Postcards and even ceramic pitchers sold well in the 1800s, but perhaps the longest-lasting tributes to the scene are the poems it inspired. Many visitors to Franconia Notch used the same straightforward title as Mrs. Eddy’s for their verses.

CLICK HERE to learn about Mrs. Eddy’s connections to fellow poets who wrote about “Old Man of the Mountain.”

Fresh audiences

In the 1850s, “Old Man of the Mountain” and another of Mrs. Eddy’s early poems, “The Valley Cemetery,” were republished in various editions of the anthology Gems for You: From New Hampshire Authors. In 1903, Mrs. Eddy’s secretary Irving Tomlinson came across Gems for You and presented her with a copy.

“Having entirely lost track of these old poems of hers Mrs. Eddy was delighted with the little book,” Mr. Tomlinson recounted.16

Mrs. Eddy herself had looked for the book decades before. In 1868, she had written to her friend Sarah Bagley, “I have tried earnestly but in vain to procure a volume of poetry in which there are contributions of my own but the work ‘Gems for You’ which I intended to send you I can not find.”17

About the time Mr. Tomlinson found the book, a 1902–03 series of articles by Mark Twain had criticized Christian Science and Mrs. Eddy. Another literary critic had also recently dismissed her as “ignorant” and attempted to attribute Christian Science to Ralph Waldo Emerson.18 In a note to Mrs. Eddy, Mr. Tomlinson had observed that her inclusion in this book of respected New Hampshire writers offered “another conclusive witness of your standing in literature years previous to your work in C.S.”19

Mrs. Eddy responded at the time to the criticism in the press, but Twain’s articles were republished as a book in 1907.20 Then, in 1908, an article appeared in The Boston Globe titled “Mrs. Eddy’s Poem,” reprinting “Old Man of the Mountain” from Gems for You and pointing out that it was “likely to prove of much interest to followers of Mrs. Eddy—and also to those of her critics who have put forth the claim that she never showed the possession of literary ability until she published the first edition of her ‘Science and Health’ in 1875.”21

Inclusion in Poems

The two poems that had resurfaced from her youth thanks to Mr. Tomlinson would end up being shared yet again, this time in her own book, Poems, published in 1910.

When Mrs. Eddy decided to compile the slim volume, she took pencil to manuscript to revise a number of the poems, including “Old Man of the Mountain.”22 She corrected what appears to have been a printing error in Gems for You, which opens with, “Gigantic size, unfallen still that crest.” When “Old Man of the Mountain” was originally published in 1844, the phrase was “Gigantic sire,” not “Gigantic size.” Mrs. Eddy also used the phrase “Gigantic sire” in an undated handwritten version.23

Additionally, she changed a description from the Gems version—“The stars, so mildly, spiritually bright”—to “The stars, so cold, so glitteringly bright.” And rather than saying the stars in the morning “mix with their more genial, mighty ray,” she clarified that they “Yield to the sun’s more genial, mighty ray.”24

“Old Man of the Mountain” was the opening poem in the new volume. In a 1910 editorial in the Christian Science Sentinel that announced the publication of Poems, Archibald McLellan remarked on its “lofty note of inspiration and grandeur of concept.” “Old Man of the Mountain” had never appeared in the Christian Science periodicals, and the book introduced it, while also including many of their Leader’s poems that readers had loved before.

“[T]hese rare gems of true inspiration,” Mr. McLellan wrote, “tell of God’s kingdom ever with those who have eyes to see and ears to hear its message. …”25